Edited and Compiled by: Benegal Pereira

I have sought to focus this compilation essentially on Apa Pant’s period in East Africa. To this end, the material includes details about his life and work before his assignment, and there is little dealing with the long period thereafter. I would like to thank all the following persons who assisted me with producing this compilation: Zahid Rajan who as publisher of Awaaz first suggested this topic to me several months ago, then gave me the benefit of several postponements because of other work pressures and finally pushed me to complete the task; Mrs. Leela Patel, a very close friend of Pant together with her late husband Suryakant starting with his period in East Africa, who was kind enough to provide me with many of the photographs supporting this commentary; Aditi and Aniket Pant who put up with my constant barrage of emails and requests for photos. Robert Gregory and Peter Wright for meeting with me and sharing their first hand experiences, having had long standing personal contacts with Pant before and after his East African tenure for their contributions as well as many interesting conversations over past years; and Angelo Faria who had lived in Kenya during Pant’s tenure, with whom I had a substantial interaction during this compilation, and for the substantial analytical piece (and rebuttals) that he prepared at relatively short notice and within tight deadlines.

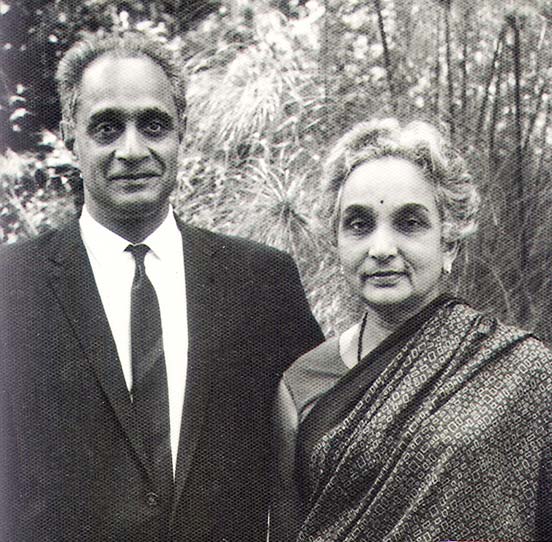

In August 1948, less than a year after the attainment of Indian independence, a still deeply British colonial Kenya colony with its Asian minority who were almost wholly British rather than Indian citizens, made its first acquaintance with an engaging and charming couple, an aristocratic Indian and his medical surgeon wife – Apa and Nalini PANT. Although their arrival was marked by high positive expectations among the Asians and a distrustful respect by the local colonial authorities, by its end about 5 3/4 years later in February it was to be a valuable learning experience for both parties. Sri Apasaheb Pant, an Indian prince and son of the tenth Pant-Pratinidhi and ruler of the kingdom of Aundh, moved by the idealistic calls of Gandhi to national service and of Nehru to diplomatic duty, left his father's state of Aundh to become the first Indian Commissioner for East Africa (Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika and Zanzibar); within a couple of years, his mandate would be extended to cover British colonies in Central Africa (Northern Rhodesia, Southern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland) and eventually the Belgian colony of the Congo.

Bio-sketch:

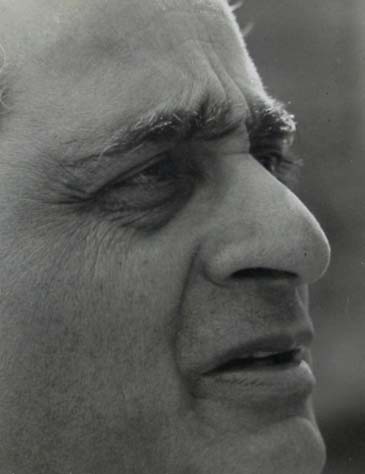

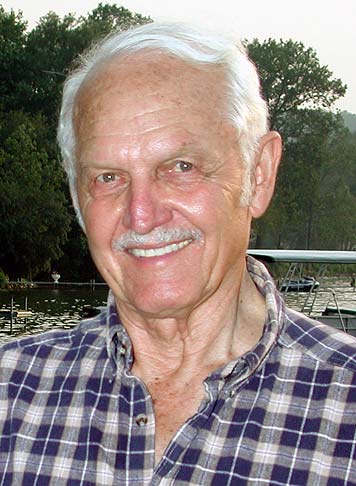

Sri. Apa Sahib Pant was born on11th September 1912.

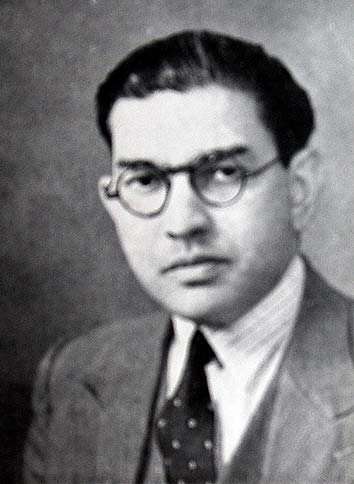

Educated: at University of Bombay (BA) and Oxford University (MA); Barrister-at-Law, Lincoln's Inn; return to India in 1937.

Award: Padma Shri 1954. Married: 1942 Nalini Raje, M.B, BS, F.R.C.S

Children: Aditi, Aniket and Avalokita Interests include: Photography, yoga, tennis, skiing and gliding.

Died: Apasaheb Pant died 5th October 1992.

Diplomatic Career:

Pant's training in the arts of diplomacy began much before his arrival in East Africa. Indeed, before Indian independence he had already served as Education Minister and Prime Minister of Aundh State (1944/45) under his father's tutelage, andimmediately thereafter he had been deeply engaged in the discussions leading to the integration of his state within the Indian Union. He wrote: “life is a constant arrival and departure, whether the journey is from one room to another or from one continentto another”. His subsequent diplomatic career spanned some three decades, during which time he was drafted into increasingly delicate and senior diplomatic assignments. These covered: Officer on Special Duty, Ministry of External Affairs 1954/55 when he worked directly with Nehru on matters relating to the Nonaligned country group resulting from the Bandung Conference in 1956; Officer in Sikkim and Bhutan with control over Indian missions to Tibet (1954/55) when relations with China were tense, especially after the defection to India of the Dalai Lama; followed by ambassadorships to Indonesia (1961/64), Norway (1964/66), Egypt (1966/69), United Kingdom (1969/72) and ending with Italy (1972/75).

Pant is the author of several books, all of which offer glimpses to his time in East Africa, these include:

An Unusual Raja - Mahatma Gandhi and the Aundh Experimen, Hyderabad: Sangam Books, 1989.

Surya Namaskar, an ancient Indian exercise, Bombay, Orient Longmans, 1970.

A Moment in Time, Bombay: Orient Longman, 1974.

Mandala: An Awakening, Bombay: Orient Longman, 1976.

Survival of the Individual, London: Sangam Books, 1983.

Undiplomatic Incidents;. Bombay, Orient Longman Limited, 1987

An Extended Family of Fellow Pilgrims,. Bombay, Sangam Books, 1990

Early Life

On Aundh:

Aundh a small princely kingdom, now situated in the state of Maharashtra, about a hundred miles south east of Poona. The story of Aundh goes back more than four hundred years back to the middle 17th century in about 1630. Its founder, Trabak Pant Pratinidhi, a poor Brahmin, turned warrior during the period of Sambhaji Raje and Rajaram Maharaj. The story of Aundh ended almost four hundred years later in 1951, with the death of Raja Bhawanrao Pant-Pratinidhi, also known as Balasaheb, the last Raja of Aundh (Apasaheb’s father). At the earlier urging of the Mahatma, Aundh was absorbed into free India on March 8, 1948. Apa Sahib Pant, a prince of the Pant dynasty was the second son of Raja Bhawanrao Pant. Bhawanrao or Balasaheb, was Apa Sahib’s father, and referred to him affectionately as his Baba. Mahatma Gandhi’s ideas about how he envisioned democracy in India took root in Aundh. Discussion between the Mahatma and Pant's father, Raja Bhawanrao and later Pant himself later evolved into ‘Aundh experiment’, designed to experiment with decentralization of democratic decision making in Aundh. After Apa Sahib returned home from his studies in England, Maurice Frydman, who Apasaheb referred to as genius, a saintly social worker, engineer and friend of Pandit Satwalekar, urged Balasahib to give up all power to the people of Aundh. Apa Sahib recounts a conversation with the Mahatma in the context of Aundh. The Mahatma said: “tell me, after being called to the bar and spending the money of the poor peasants of Aundh on yourself for five years, are you going to migrate to a city such as Bombay or Delhi and make money by exploitation? Or have you any sincere sense of obligation, of doing your duty, dharma, by serving the poor people of Aundh, who have until now, fed and clothed you?” Apasaheb’s quite taken aback by this direct question replied: “Bapuji, what can I say? I would certainly like to help my old father, and stay on in Aundh. At least such is my present inclination”. The Mahatma smiled, and said, “Look Apa, you are dealing with me now. My old friend Pandit Satawalekarji has written to me that your father wants to hand over the kingdom of Aundh to his people. I hope this intention is genuine. It would be truly in keeping with our ancient customs which follow by those good rulers who knew what their dharma was……” Peter Wright, a long standing and close English friend of Pant from their university days at Oxford until Pant's death, and followed him to India during the II World War period through Indian Independence and Kenya in the early 1950s,and after his deportation in 1952 back again to India,, wrote: “I am well aware of Apa's feelings with regard to the absorption of the small state of Aundh into the Bombay Presidency and subsequently into the state of Maharashtra. I visited Aundh when Apa himself was the Chief Minister and had, with enthusiastic local support, transformed it into a tiny model democratic state -- an outstanding success -- with the full support of his father. He [Pant] has never been given the recognition he deserved for doing this; incidentally it also led to a number of Indians from outside, who were "wanted" by the British authorities for political reasons, taking refuge in Aundh State. Also I am not aware that Apa has been given adequate recognition for his hard and in the circumstances painful work that he did in helping to persuade other Maratha princes to surrender their sovereignties to the newly forming Indian Union Government in the interests of constructing a truly united and democratic state. Pandit Nehru was, of course, well aware of this when he selected Apa for the Nairobi position”. The clash between Shivaji's militaristic views and Gandhiji's pacifism, inevitably affected both Apa and his father, with the Gandhian views finally triumphing (as they did with Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan in the NWFP). I personally felt immensely privileged v to know and to have the love and friendship of this great duo, father and son, and to learn from them something of the great Maratha history and traditions.

On Leaving Aundh for East Africa (1947 – 1951): © Pant, Apa; An Unusual Raj, Sangam Book, 1989

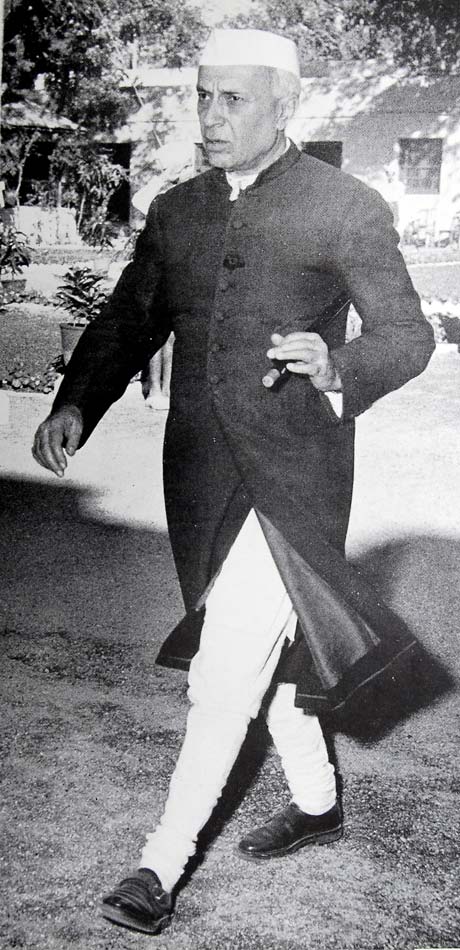

Apasaheb’s expressed his emotional feeling at the start of his diplomatic career, when Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru offered him his first diplomatic assignment – as first ambassador of free and independent India to colonial East Africa. It was in December of 1947 that Apa Sahib was summoned to go meet with Nehru in Bombay. Pant said, “Doors that open unexpectedly are not always easy to pass through”. His energies had been in a state of dull suspension, given the prospect and dissolution of Aundh, but were stirred again as Nehru asked him “Apa, go to East Africa and be our first representative”. He later recounted: “ To be a representative, a Pratinidhi as in our family tradition, was not only exhilarating in a personal way but something I had felt my father would welcome for his son, an honor that would be his as well as mine. But the merger of Aundh had left many problems for the family, and not all of them had been settled”. Later, in New

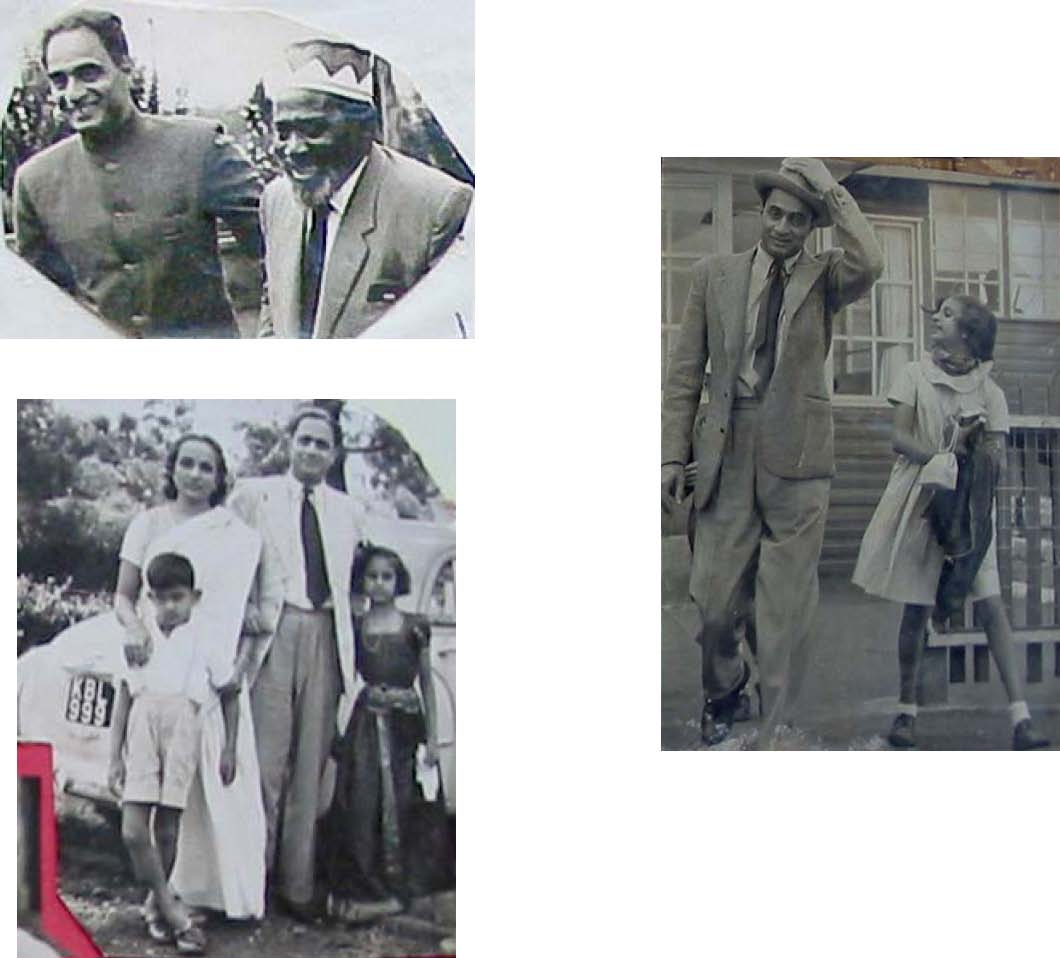

Delhi, when taking leave of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Pant told Nehru that he knew nothing of diplomacy, or of Africa. “Never Mind”, Nehru said jokingly, “Go and shoot a few lio ns!” Pant said he did, many of them with a camera, of course. In this and in every way it was a terrific experience. And he wanted his father to share in it; In 1950 Pant’s father paid a visit to Nairobi. Apasaheb’s speaks:

ns!” Pant said he did, many of them with a camera, of course. In this and in every way it was a terrific experience. And he wanted his father to share in it; In 1950 Pant’s father paid a visit to Nairobi. Apasaheb’s speaks:

Apa Sahib speaks:

“By the end of 1947, Nalini and I left Aundh. That last day in Aundh is still vivid in my memory. I could not believe that I was leaving Aundh for good. All the pots and pans, beds and cupboards and chairs were loaded on to a state-red number plate truck.

Baba, with his red cap, had come out of the palace to bless his daughter-in-law and me, and our little, sweet four year old daughter, Aditi. Baba was happy and also sad. Happy because his daughter-in-law was to start practicing medicine and surgery in Poona - She had built a house there on the plot given to her by her father and mother. And sad because little Aditi was also leaving.

I tried to settle down to a routine in Poona at the end of 1947. I did not know what to do. Someone suggested that I stand for the constituent assembly from the Deccan state constituency. I did, but failed to get in by one vote. Shri Munavalli won against me. So I retired even more into my minuscule ego.

It was Raosaheb Patwardhan who, like the affectionate elder brother that he was, dragged me out of my hole, and forcibly took me to see Jawaharlal Nehru in Bombay. I was of course, very hurt that the congress, and the high command had completely forgotten what Raja Bhawanrao had done for the freedom struggle and I secretly hoped that Baba would at least, be made a raj pramukh if not given a ministership.

But who would care for Aundh when even the Mahatma was forgotten? So when Raosaheb ushered me into the presence of the shinning, smiling, extremely self-assured first prime minister of independent India, I was aggrieved.

Panditji however could charm anyone, any time, with hardly any effort. He was then at the height of his power.

When Raosaheb asked him if he had forgotten me, he said, “No, I was just thinking of him just the other day.” Then turning to me he said, “Apa, go to East Africa as our first ambassador there.”

Ambassador? I was to be an Ambassador? I should have shouted for joy, but didn’t feel like it then. My ego would take a while to assert itself again.

I asked, “What do I do there as an ambassador, sir?” Mischievously Panditji said, “Oh, nothing much! Giver dinners, and perhaps shoot a few lions (With a camera, of course).” So I sailed alone by the S.S.Khandala, the oldest ship of the P & O line. Baba and the rest of the family were there to bid me farewell. Was Baba proud that I, his second son was now an ambassador of free India?

Was I happy and proud? Hardly, I was disgusted with myself. I did not like leaving Baba all alone.

As I boarded the ship, I wept. Tatya Inamdar was to accompany me as my private secretary. It was Nalini’s idea and she had persuaded Jawaharlal to agree to it. It was quite unusual for a person outside the I.F.S. or the secretarial cadre to be appointed to go abroad at the Government of India’s expense, and everyone must have thought that it would serve me better if I had a wiser person to guide me. Tatya, as usual, did so with care and affection. I missed Aundh, Baba, Nalini, Aditi and little Aniket, our son who was then just a year and a half old.

Understandingly, Nalini scarified her own career as an honorary doctor ate the Sassoon Hospital in Poona, not to mention her professorship and budding practice, to join me in 1949. Thus Aditi and Aniket grew up amongst lions, rhinoceros and zebras. Those five and half years in Africa where glorious for us.

Once again I was filled with new motivation. My ego re-inflated itself and I wanted Baba to see me confident once more. So Baba came to stay with us for a while. He travelled widely

in East Africa and was happy. He was especially fond of little Aniket. Aditi was too volatile for his liking.”

Apa on Nalini © Pant, Apa; An Extended Family of Fellow Pilgrims; Sangam Book, 1990

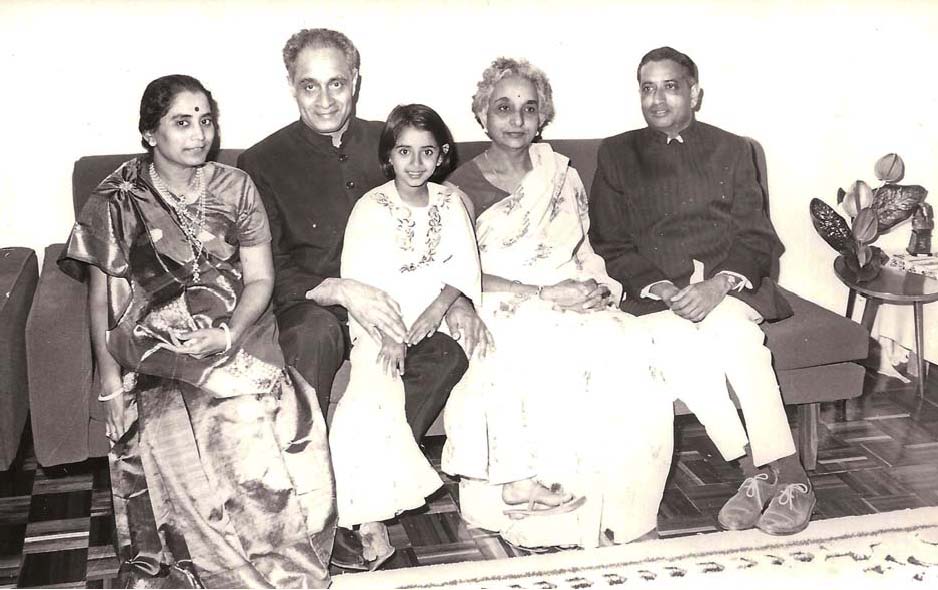

The longevity and synergy of the Apa –Nalini partnership, and its resulting legacy, is a tribute to the symbiotic relationship between Apakaka and Akka, respectively (as they lovingly referred to each other).

Apakaka’s initial encounter with Akka was at her eldest brother’s small two room flat in Bombay. It had been preceded by a meeting he had with Natesh Appajii Dravid, Akka’s father, who had first come to meet him as an eligible bachelor in Poona the previous year to make a proposal of marriage. At this time, after having secured her fellowship in Surgery (F.R.C.S.) in Scotland, she had been appointed to head of a women’s hospital in Rajasthan. Curiously, Apa and Tai Dravid, Akka’s mother, had a brief letter exchange five years earlier, when she wrote him stating that she had: “watched (my) career with interest”, so Apa appears to have been tagged much earlier as a potential son-in-law for the well suited and educated Nalini.

Apa confesses that at this very first meeting with Akka he was “…deeply impressed by her apparent calm and dignified bearing, her high intelligent forehead, her sharp, steady, critical, non smiling, even stern, but kindly eyes..” But the spell was broken when “going to the kitchen, she banged into a wooden screen in front of the door”.

Apa Sahib speaks:

“Each one of us, whether it was Africa or elsewhere, looked at the same event or people from different angles. In any case no two people can even share the same point of view of life. Our view points were different – often clashed – but our objectives were the same: making friends for India and building a world network of mutual understanding. It was, of course, a fascinating task. It was very joyful and fulfilling too. At the end of it, we both felt we really had lived.

From Pandit Nehru, Indira Gandhi, to Aditi, Aniket and Avalokita, all felt that what I said or did had to have the final stamp of Akka’s approval! In fact in 1958, Pandit Nehru whilst staying with us in Gangtok, asked Akka whether she had read ‘that stupid report of your journey in Tibet by Apa?.’ He also asked her, ‘Do you approve what Apa does or write?’

Indira had a especially soft corner for Akka as did all the various ministers, such as Swaran Singh, Jagjivan Ram, Subrahmanyam and others. All the foreign secretaries would, in half-joke half-serious, manner, ask Akka to control me!! She did, magnificently’

They spent the first five years prior to 1946 in the Aundh, where their two first children were born, Aditi and Aniket, and later their third child Avalokita. After a short interval in Poona where Nalini had to give up her job at the Sasson Hospital as well as her private practice, for the start of the Pant’s first diplomatic assignment, and as commissioner for East Africa.

Apa Sahib speaks:

“Akka can be merciless in her criticism. Her objective is not to put down or show one in a derogatory light, but to help one correct oneself: to help one to strive even harder. People like me are over generous with compliments and approvals. Our approval therefore has little value. People like Akka on the other hand are frugal, sparing in theirs, therefore all seek them and feel fulfilled when they receive them”.

“Akka has been the greatest, the most persistent, ceaseless but loving, image smasher of all! Pretence, inadequacy, hypocrisy, falsehood of any kind, she could never tolerate, and said so openly and instantly. What a fellow Pilgrim she has been” (Pant).

As one lives and experiences same or similar situations, one’s mental and intelligent vibrations start to respond to the person most intimate to oneself. Words then become unnecessary. Between Akka and me it has been so far for the last so many years. Thoughts, feelings, just get transferred spontaneously. It is great fun!! It is also a discovery of some aspects of that unified mind-energy in which we exist. Akka of course has helped me tremendously in this self-discovery.

Pant’s tenure as India’s first Commissioner for East and Central Africa, as it relates to Kenya: a personal interpretation. (Personal Communication from Angelo Faria: November 2007)

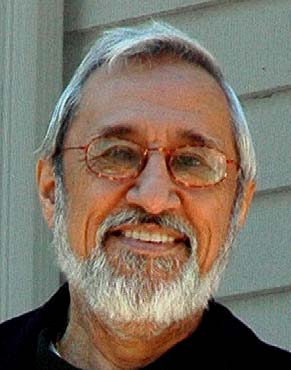

Angelo Faria was born to Goan parents in Mombasa and completed his secondary schooling in Kenya. He went on to obtain undergraduate and graduate degrees in economics, respectively, as a Kenya Government Bursar and Leverhulme Undergraduate Scholar at the London School of Economics in the United Kingdom in the 1950s (where President Mwai Kibaki was his exact contemporary) and as a Ford Foundation Fellow in the U.S. at the University of Wisconsin (Madison) in the 1960s. He was first employed as a senior official within the erstwhile East African High Commission (EAHC)/East African Common Services Organization (EACSO) in Nairobi for just under a decade. Thereafter, and following a short two-year spell with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in Lusaka, Zambia, he was for about 30 years a staff member of the International Monetary Fund in Washington DC. He retired from it in 2003 and currently resides in Washington DC. He remains keenly interested in, and is a perceptive private commentator on, the East African political environment, through continuing personal contacts and periodical visits.

I. Introduction

My evidentiary background in preparing this piece is relatively modest and somewhat informal in character, being limited essentially to prior information on the evolving political environment in Kenya especially as it impacted on Asians acquired, inter alia, from having lived in Kenya both before and after independence, engaging over several decades in wide-ranging conversations with others, and reviewing cursorily earlier academic books published in the 1980s including : Dana Seidenberg (Uhuru and the Kenya Indians, 1983 and Mercantile Adventurers, Ch. 6; 1996) out of the University of Syracuse in the United States and J.M. Nazareth (Brown Man, Black Country,1981).

It is also buttressed by my more recent reading in March/April this year through incomplete sets of past Kenyan newspapers covering the period 1949-54 (East African Standard, Colonial Times, Daily Chronicle, Goan Voice and Daily Mail) that I found serendipitously in the US Library of Congress here in Washington. This was piqued by a spate of recent “revisionist” academic books published in the last three years: James Franks (Scram from Kenya, 2004); Caroline Elkins (Britain’s Gulag, 2005); David Anderson (Histories of the Hanged, 2005); and Zarina Patel (Unquiet, 2006) and an incomplete set of material copied to the UK India Office titled: “Kenya Colony Intelligence and Security Summaries Reports (1947-49”) which was released in 1998, and received recently during several interesting discussions with Pyralli Ratansi. More recently still, through the personal courtesy of Benegal Pereira, I have read through the relevant sections relating to Pant’s tenure in East Africa weaved by him in his four books: A Moment in Time (1974; Chapter Four); Mandala (1978; Chapter 2); Undiplomatic Incidents (1987; Chapter 1); and An Extended Family of Fellow Pilgrims (1990; Chapter 11); these have helped me to enable Pant’s own words, as reflected in numerous quotations (in which errors in the spelling of proper names are left unchanged) to be inserted in the text, so Pant could, as it were, be allowed to speak for himself with the benefit of considerable hindsight..

The outline of political developments in Kenya generally are thus well known from published sources; that relating to the impact of such developments on the Asian community is perhaps less well explored (apart from Seidenberg’s books), and in particular the role played by Pant which is of course the central concern of this piece. In this respect, Pant’s own evaluation interspersed through his books, although profiting modestly from the passage of time, is curiously more anecdotally than substantively reflective. As a result, I have had to try and first to sketch out with a broad brush the political environment Pant faced on his arrival and its evolution during his tenure; my effort is, therefore, counterfactual in the sense that it attempts to understand Pant’s private thinking of political developments as these evolved, as if Pant was a central player which of course he was not.

I am fully conscious that this is not the standard “scholarly” contribution, annotated by fuller reference to the extensive relevant literature that has emerged, and backed by associated citations (other than for quotations from books written by Pant noted above, which are specifically referenced by year of publication and page). These quotations are useful as providing some indication of Pant’s thinking at the time, but they provide in my view little indication regarding his perceptions about whether his exhortations were influencing the racial groups (especially Africans) to whom they were addressed at the time. Moreover, with one notably short exception (see my conclusions section), there is very little by way of balanced reservation arising from a consideration of subsequent developments in his ex-post analysis of his thinking of the period.

If the piece is not scholarly, it is only because, for several personal and time-related reasons, I have been unable to commit myself to an authoritative survey of the relevant materials. As such, this piece constitutes an entirely personal and somewhat inferential interpretation exclusively from Pant’s supposed perspective, but limited essentially to Kenya rather than to the wider geographical sphere to which he was accredited. I believe that the modestly revisionist case I make out is at least plausible on its face. I fully recognize that there is, however, always the distinct possibility that some of the inferences from an admittedly modest factual base that I draw may be prospectively invalidated by more knowledgeable contributors and even from the discovery of countervailing factual information.

In this first section, the emphasis is on delineating in general terms the environment that Pant, a diplomatic neophyte, would have found when he first arrived in Kenya in mid August 1948. In the second or evaluation section the emphasis shifts to consider more specifically Pant’s strategy and activities as these evolved during his tenure in Kenya, so far as I have been able to gauge these from his writings and my own inferences.

II. Background

Pant arrived in Kenya by ship on August 15, 1948 to much fanfare on his initial appointment as Commissioner of India to East Africa, his mandate gradually being widened to include Central Africa in 1950 and the Belgian Congo in 1952, and his designation concurrently being upgraded to Commissioner General; he was eventually to vacate his appointment under much less auspicious circumstances some 5 ½ years later at end February, 1954. While Pant’s remit grew wider over the term of his assignment and the paths traversed by these countries resulted in the same outcome of eventual political independence from British rule, there were important differences as between them; these related to both the nature and speed of this process, tied to the presence in their populations of white immigrants, as well to their legal status of colony (e.g. Southern Rhodesia and Kenya) versus protectorate or UN mandated Trust territories e.g. Uganda and Tanganyika and Ruanda-Urundi).

Two factors were, I believe, nevertheless critical in explaining why Pant’s own diplomatic activities should have been centered largely in East Africa, and within it mostly to Kenya. First, the relative numbers of residents of Indian descent in Pant’s remit (hereinafter Indians or Asians), although the number of them actually holding Indian rather than British nationality was, at best, rather miniscule. The numbers of people of Indian descent at end 1952 (as reported by Nehru in a response to a question in the Indian Parliament in 1953) were estimated as: Kenya: 152,000; Uganda: 33,367; Tanganyika: 56,499; Zanzibar and Pemba: 15,812; Northern Rhodesia: 2,600; Southern Rhodesia: 4,150; Nyasaland: 4,000;

Belgian Congo: 720. What this suggests is that Pant’s leverage in the British territorial regions outside the East African, premised on the number of their Indian residents, would have been at best exiguous. Moreover, even within the four distinct East African territories, it was clear that the issues which bedeviled the interactions in racial terms between European or native British citizens and Non European or non-native British citizens were present to a much less significant degree in the other three East African countries as compared with Kenya. This was attributable initially to the former’s somewhat different legal status as protectorates or trust territories relative to Kenya as a colony, and later to the broadly satisfactory progress that was being made within them towards constitutional reform leading to self government and eventually to full political independence.

Kenya’s case was, of course, an entirely different one, for reasons that are already too well known in the published literature to warrant being extensively detailed here. Briefly put, Pax Brittanica provided the bedrock assurance to emigration for long term settlement in the 20th century from both the United Kingdom and the Indian sub-continent, stemming largely from intrinsically economic motivations. This applied to the successive waves of European immigrants in the 20th century, accentuated for periods immediately following upon the ending of the First and Second World Wars, who engaged in agricultural, larger business and higher level government-related activities. It extended also to a steady stream of Asian or Indian immigrants that flowed in, starting with the construction of the Kenya/Uganda Railway and expanding into associated retail trading lower level governmental cadres, and the service sector generally.

Second, the interaction between Europeans and Asians on inequitable terms -- the numerically dominant Africans being treated at this stage in purely residual terms for policy purposes – had produced inter-racial flash points already in the 1920s especially in Kenya. (There were contemporaneously, of course, some minor difficulties associated with the ginning of cotton in Buganda by Indians). It has since been suggested that to head off any incipient agitation by Indians, at the request of the “settler” Europeans the United Kingdom government issued the notorious British White Paper in 1923 (also known as the Devonshire Declaration) which led to the defiant nonpayment of poll tax by several Indians in 1924. It asserted baldly the paramount nature of safeguarding the interests of the African majority as the overarching objective of colonial policy in Kenya. Later in 1934, then Colonial Secretary Ormsby Gore would even go on record as stating that he regarded Indians as “mere interlopers in a country that belonged only to Africans and Europeans”.

Indeed, it was precisely such considerations that, long before their own political independence in 1947, attracted the interest and concern of the British Imperial Government as well as the solidarity of (non Muslim) politicians in India. Initially, this resulted in several Indian ICS officials (Srinivasan, Menon) coming out in the early 1920s out to examine and report on the conditions faced by Indian labour in Kenya. Eventually this would lead even to the presidency of the East African Indian National Congress (EAINC), modeled on that of the Indian National Congress (INC), being offered on a non residential basis to first Mrs. Sarojini Naidu (1924 and again in 1929) and subsequently Pandit H.N. Kunzru (1928 and 1929). It is moreover sometimes glossed over that the decision to nominate Pant as Commissioner of India for East Africa represented a direct response by Nehru to the formal request made earlier to the INC by the EAINC in September, 1946 during its 18th annual session in Mombasa.

It seems to me upon reflection that the evaluation of Pant's almost 5 1/2 years tenure in Kenya can be regarded as being largely influenced by the continuing interplay of five factors whose very rank ordering in importance understandably changed during the period of Pant’s tenure:

First, the degree of interest shown by India and specifically Nehru in speeding up the process of decolonization – a task for which the Labour Government was to prove a most accommodative partner, as this was the chief foreign policy tenet of the Fabian socialist creed with which it was imbued. In this context, I believe that as far back as 1937 Nehru, as the principal foreign policy spokesman of the Indian National Congress, had come to see that Indian emigrant minorities in colonial territories needed to be suitably sensitized to the importance of respecting and identifying with the aspirations of the majority population. One comment of Nehru to Pant bears quoting: “We Indians are in the middle…and we have a chance, a duty, to try and prevent the growth of a racial conflict” (Pant 1974, p.50). But while decolonization may well have been Nehru’s primary foreign policy preoccupation soon after Indian independence in August 1947, nevertheless by the early to mid 1950s and as India’s world role grew, this gave way gradually in his mind to a greater focus on political solidarity within a wider, so-called non-aligned comity of developing nations, some of which were former colonies.

This change of focus crystallized in India’s formulation of the regional Panchsheel principles with China over Tibet in June 1954 and the Bandung Non-Aligned Conference in April 1955, in which Pant was to play a prominent advisor’s part. It represented Nehru’s evolving philosophy of searching out for an independent “third way” for the newly emerging developing world away from the consuming rivalries of the United States and the Soviet Union as leaders of the two super power political blocs; in the nonaligned movement, while Nehru was undoubtedly the principal initiator, he came soon to be joined by presidents Nasser of Egypt, Soekarno of Indonesia and Tito of (then) Yugoslavia.

Second, the nature of the interaction, varying from initial tacit acquiescence or indifference to subsequent heightened tension, as between the United Kingdom and Indian governments relative to the assumption by India of this anti-colonial, nonaligned role --- in particular, its repercussions on Pant’s activities in at least their East African colonies. For his part, Nehru, as Pant has noted, Nehru always viewed the state of his relations with the Commonwealth Relations Office as a constructive part of his foreign policy. In practice, however, this interactive variance turned upon which among the two UK political parties, Labour (November 1945 – November 1951) or the Conservatives (November 1951 to the end of Pant’s term and beyond), were in power in London.

On the political front, Labour, influenced by its Fabian intellectuals, was clearly more anticolonial and pro-independence minded than the Conservatives, and their recent experience with granting of political independence to India and Pakistan had imbued them with the desire to hasten the process in their African colonies also; on the other hand, the Conservatives, in part from sentiment and in other part from having observed the effects of Partition on the Indian subcontinent, seemed still emotionally unprepared to contemplate an unseemly rush to dismember the British Empire, on which at one time their proud boast was that the sun never set completely on the whole of it.

On the economic front in addition, Labour held fast to the so-called Fabian socialist tenets about production and distribution, income and wealth, and the role of the government versus that of the private sector in providing economic with social justice for the common man; in marked distinction, the Conservatives emphasized individual freedom and liberty over intrusive government in economic matters, underpinned by minimally regulated free enterprise, price setting in open markets rather than artificial price fixing, and production incentives for risk-taking entrepreneurs. In many ways, the ideological struggle brought about by Labour’s first ever election victory in the UK was initially transmitted to the administration of its colonies also.

Third, the extent of local European reaction in the colonies was generally influenced on the “official” side in principle by the philosophy of the incumbent UK government (in particular, the persona of its Colonial Secretary) and in practice of course by the personality of the incumbent Governor charged with implementing stated policy; in a very real sense, therefore, colonial policy formulation and its implementation thus reflected the interaction between them. The “unofficial” side, of course, incarnated the beliefs of the white "settlers" against any dilution of their power through any equity-based power sharing agreements with the other two numerically larger races. In this connection, the Asians in particular were always perceived, by virtue of their older culture and more pronounced economic wealth, to be far and away the more imminent threat, relative to the vastly more numerical but unorganized and less well-off Africans. Moreover, European dislike of the Asians accentuated after 1947, now characterized by a greater distrust of the intentions of non-Muslims relative to Muslims largely because India and Nehru were viewed with greater distrust amounting to fear than were Pakistan and Jinnah.

It is striking in retrospect to establish that in 1949 the relative numbers in each of the four East African territories of European and Asian residents, respectively, were (multiples of Asin/European in parenthesis): Kenya: 29,660 and 152,000 (5.1); Uganda: 3,448 and 33,367 (9.7); Tanganyika: 10,648 and 54,499 (5.1); Zanzibar and Pemba: 548 and 15,812 (28.8). Asians to Europeans was a multiple of 3 or greater total population. Much more striking of course, other than in Zanzibar and Pemba where Arabs predominated), the combined population of Europeans and Asians represented some fraction of 1 percent of the total population, thereby pointing up starkly the sheer numerical predominance of the indigenous African population and their corresponding virtual absence from representation in the political and economic life of these four countries.

Fourth, initial expectations formed among the local Asian political and business representatives about Pant’s role. While it was almost euphoric at the start of his tenure, as Pant himself noted (Pant 1987; p. 16/17), it remained of course to be seen to what extent they would duly buy into Nehru’s message, quite appropriate and consistent for him but unsettling for them, which was to entail a radical re-ordering of their objectives. Here of course, in addition to the perennial problem about European/Asian relations from the early days, there were the likely consequences of the creation of India and Pakistan as new nations carved out of the subcontinent in 1947, based at least for the latter on a theocratic principle. This could only exacerbate communal tensions, previously relatively muted, in the form of separate communal rolls that would undoubtedly benefit the divide and rule policy of the British administration, notwithstanding the fact that about 80 % of the Muslim residents (including Ismailis) hailed from post-Partition India. In any event, Pant by virtue of his much earlier arrival became effectively the sole Asian sub-continental diplomatic representative during his whole tenure because the first Pakistan Commissioner (Siddik Ali Khan) did not arrive until December 1954, long after Pant had left. Curiously though, in late 1948, perhaps as a reaction to Indian independence, Portugal for the first time saw fit to appoint a Consul General (Jose de Neiva) to provide consular services to, and look after the general interests of, the Goans who were overwhelmingly Portuguese citizens by birth or registration.

Fifth, the degree to which local African politicians looked to India (rather than Pakistan) and thus to Pant for ideological and material support in their colonial struggle for political independence. At Pant’s arrival, there would appear to have been a somewhat superficial albeit non-tribal organizational cohesion, as represented by the Kenya African Union (KAU) which in 1945 had been broadened from the decades-old Kikuyu Central Association (KCA). This had been undertaken with the active support of the then Paramount Kikuyu Senior Chief Koinange-wa-Mbiyu so as to attract a wider base, including especially non-Kikuyus, in the face of the intransigence displayed by the British administration on the land tenure issue in the area (essentially the Kikuyu heartland) which later came to be known as the “White Highlands”. It was galvanized into action by the return in late 1946, after a self-imposed exile in Europe of some 15 years, of Jomo Kenyatta who took up its leadership in 1947 and married Koinange’s eldest daughter in the same year, thereby insinuating himself into the center of the Kikuyu land struggle. Apart from Kikuyu leaders like Gicheru and Kaggia, however, there was also a coterie of other non-Kikuyus such as Oneko, Kali, Josiah, Khamisi, Kasyoka, Mbotela, and Odede. Nevertheless, the agitation remained a narrowly tribal one -- essentially among the Kikuyu and grounded in their claims to Kikuyu tribal

land. While India through Pant may initially well have provided a psychological boost to the African cause and some journalistic material and financial assistance in publicizing the land issue, once the struggle turned violent it is not clear what became the nature and extent of Indian support and of its channeling. In this connection, Pant cryptically notes: “ .. the colonial government could not pin onto the Indian mission any specific act of iciting the Africans against British rule, through a public speech or a secret gift of arms or ammunition to the Mau Mau”, (Pant 1987; p.25).

Whereas in principle the focus still remained on Kikuyu tribal land issues, operational activities extended to the recruitment of some cadres in the rural areas, and a modest degree of cyclostyle-type pamphleteering and vernacular newspapers, to advertise an extended range of issues to a wider African audience outside the Kikuyu heartland. The expansion of such dissemination activities were initially constrained by financial means as well as the very close monitoring and circumscription by the authorities.. Later by early 1952, the focus would change towards a more violent, and very tribally limited, uprising that moved from around the greater Nairobi area into the Aberdare forests in the Kikuyu heartland, when it came to be better known as Mau Mau.

III. Evolution and Evaluation of Pant’s tenure

Against this background, it seems to me not implausible to suggest that Pant's tenure as Commissioner can be distinguished broadly (but not neatly) into two time-demarcated phases --- an initial phase, of a longer and markedly positive period of about 4 years from August 1948 through June, 1952, during which all the factors noted above seemed to work in Pant’s favor, thereby permitting him to walk a diplomatically fine line fairly successfully between his overarching Nehruvian mandate and the more parochial expectations and fears of the other local actors. This was followed was followed by a shorter terminal phase, of about 1 ½ years from July 1952 through February 1954 when the stars would have appeared all to have turned away from him leading him to be much less successful in his mission; indeed,, during this period, his influence inexorably drained away, culminating mercifully I believe in his sudden recall.

Pant comes across as a man with a very genuine sense of mission; as he notes, “Nehru had said ‘Befriend Africa’ and I, with my usual impulsive over-enthusiasm went about it with missionary zeal”. (Pant, 1987; p.19). The essence of Pant’s somewhat romanticized view in the matter was expressed as follows: “India and East Africa may seem to be distanced from each other by salt water. But they are, and always have been ‘next shore neighbours’, and surely their future lies in the direction of mutually profitable co-operation. From the very first day that I set foot on this ‘Continent of Dawn’ I dreamed of a harmonious special relationship between our two civilizations and peoples… and I have lived out my Gandhian dream under the skies of East Africa” (Pant 1978; p. 30 and 35). Pant was thus ideally suited to his task: that being Nehru’s hand-picked instrument --even if he brought to it a somewhat naïve Gandhian dimension or what he termed as the “Nehru-Gandhi inspired ideal of making friends” (Pant 1987; p.22) not envisaged or particularly appreciated by Nehru -- for fostering the attainment of his vision of an end to racial discrimination and colonialism, denoted as the involuntary subjugation by colonial master powers of subject peoples, both of whom were racially and culturally distinct.

In carrying out his mission, however, Pant had indubitably to tread a very fine line owing to the somewhat anomalous quasi-diplomatic nature of his office. Nehru, with his overarching objectives, had idealistically envisaged for it the remit of a broad, almost super-representational role over a wide geographical area, with some trade considerations thrown in for good measure. This ambitious role had to be reconciled in actual practice with a much lower level operational role, reduced to serving as a mere listening post or conduit to report on political developments, as well as engaging in consular activity almost wholly covering travel arrangement for the mostly British citizens of Indian descent traveling on customary temporary familial visits to India. Indeed, the overwhelming majority of such persons had little intention to acquire Indian citizenship, and this was fully exposed during the Asian exodus in 1968 when the bulk of them offered the choice opted to migrate to Europe, United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, rather than return to India.

INITIAL PHASE (August, 1948 – June 1952)

In this phase as previously noted, there was a happy confluence in the interplay of all factors noted above which made for a distinctly positive sum game for Pant in carrying out his mission --- Nehru still remained fully engaged in the decolonization exercise, in particular as it related to the British African colonies; Labour was in power for virtually the whole period, being voted out only in November 1951; Governor Mitchell’s assignment had been extended for six months in order to organize the Royal visit in February 1952 as well as to oversee the general election that would usher in the new multi-racial legislative plan in June 1952 . More importantly, he still had good relations with both Asians and Africans -- the latter, notably the Kikuyus through the Koinange family, and with them and also other tribes as represented in the labour movement -- both thanks largely to Pio Gama Pinto. They were still receptive to the general thrust of his mission, in large part because the authorities were still ambivalent about confronting the emerging signs of what later on became well known as the Mau Mau uprising.

On the work front, Pant began peripatetically by making extensive familiarization visits to both the authorities and their residents of Indian descent who were generally not Indian citizens, in the far-flung British territories under his watch; he relished these trips greatly because these opened up new vistas for him.. He did place his greatest focus, however, on delivering activities in east Africa especially Kenya, engaging in public addresses within Kenya (but never, as far as I have been able to ascertain, formally to the EAINC), as well as in private dialogue. Although these were never officially published, Pant himself realized that the details were being duly reported by informants, and subsequent intelligence reports confirm that he was correct in this assessment. He even found the time to make extensive visits through the East African countryside, in February, 1950 leading the first private Indian mountaineering team (including his wife) on a climb of Mt. Kenya (17,040 feet), where he reached a height of about 16,000 feet before retiring, and later also climbed up Mount Meru (14,000 feet) near Arusha in Tanganyika. (Pant 1987; p.30/31). Later in 1950 in the context of a visit from India by his elderly father, as well as on several occasions thereafter, he visited the various game parks to “shoot lions with my camera”, as he humorously remarked. On the commercial front, although such matters were handled by a separate Indian Trade Commissioner’s office in Mombasa established in 1950, Pant may well have played a catalytic role in January 1950 by securing the introduction of regular weekly air flights between Bombay and Nairobi by Air India; by early 1954, he likely had a hand also in strengthening ocean-going transport connections between Mombasa and Bombay through setting in train the New Eastern Passenger Service steamer using the steamer, “State of Bombay”.

Pant consistently hewed to a standard Nehru line in all his suitably nuanced public and private presentations, albeit he added his own Gandhian gloss to it.(Note that he titled the relevant chapter in one of his books as “Gandhian Dream in Africa” (Pant 1978; p.20). Following Nehru’s mandate, Pant genuinely believed that it was quite feasible to work towards a prospective multi-ethnic, multi-cultural society in East Africa if Asians were prepared to open their educational institutions to, and share economic power with, Africans; but he advocated it not merely as a form of Nehru-type political realism, but also as the basis for a Gandhian type morally- based “pilgrimage” towards the brotherhood of men of goodwill among the three races. Two quotes from Pant should suffice to capture the essence of his nuanced feelings, unchanged through time: “To me, it seemed that the immediate problem of relationship between Kenya’s Indian residents and the Africans had to be considered in the wider context of African aspirations for freedom, and of the relevance of our experiences in India to such a struggle (emphasis supplied), and “The enthusiasm of all the meetings, talks, and plans that followed was kept going, for many of us, by a feeling that the victory of harmony and enlightened co-operation over exploitation and conflicts was just around the corner”. (Pant, 1974; p. 51/52).

To this end, he counseled straightforwardly that prospective security for Asians wishing to continue to reside permanently in a future independent Kenya was crucially time-contingent, so they must remain patient and confident that positive change would come about sooner rather than later. In the meanwhile, however, they had to identify as fully and quickly as possible with the underprivileged African majority; this entailed, as a practical matter, that they should redirect themselves from their traditional quest of decades to become privileged coequals with the Europeans, who he considered largely as birds of passage, and seek new ways of participating with the majority Africans in all areas to help them to realize their full potential.

With the tenor of Pant’s general message having been clearly set out for him by Nehru himself thus permitting little creative wiggle room, Pant was effectively reduced to continually making repetitive exhortatory addresses both public and private to local Indians of all communal stripes (and perhaps even African leaders, although this is much less clear from his reporting!!) and serving as a listening post and conduit for information from the region to Nehru, when he was not traveling to “show the Indian flag” in his wide parish, as it were. There was clearly very little of substance that he could provide for the Asians in Kenya which would have corresponded to their own parochial but important concerns such as the prevalence of colour bar in service establishments, the right to freely obtain land titles for urban and rural land, and above all to secure parity in representation and treatment within the executive and legislative organs of central government and also the public administration.

Against this background, he had probably had to resort – and he would be in his element in doing this -- to maintaining very cordial social relations on an individual or small group basis with selected Asian and African leaders, exchanging with them (in particular, the Asian journalist fraternity directly or through his adept Information Officer, Shahane) snippets of information and more general assessments that could then be forwarded confidentially in his periodic reports to Nehru; indeed, it would in retrospect provide a fascinating glimpse, in generating a more accurate assessment of his thinking, if one were able to access these reports in the governmental archives in India.

Pant was evidently aware very early on of what the Asians expected from him. To quote him:“I quickly got the general drift of what the Indian population looked for in its ‘own’ Commissioner. I was to be the ‘strong man’ who would bring down the pride and exclusiveness of the Europeans and ensure equal privileges for the Indians. I must fight for more Indian seats in the Assembly and more Government posts. I must do everything, above all, to enable the Indians to make more money.” (Pant 1978; p. 22-24). What is more to the point, Pant instinctively refused to adopt this suggested role for himself, noting prophet-like “For myself, I could only shout day and night at my Indian friends that the dawn of African freedom was near and that they should wake up while there was still time to prepare themselves for it. Only a few, I’m afraid, really did wake up and even then they did not clearly see the shape of the part they would have to play in the new life of this continent.” (Pant 1978; p.24)

Asians in their turn had clearly misjudged what Pant should be able, or more importantly would choose if able, to do specifically for them on the issues noted above. This was illustrated very much earlier from the reported comment made by

S.G. Amin, the EAINC President through August 1948, at one of these public meetings with Pant in October 1948. Amin had ventured to suggest that henceforward the heavy burden carried by Indian politicians and the EAINC would rest on his (Pant’s) shoulders. Pant gently but firmly took refuge in a convenient technicality by reminding his audience that he had been sent by the Indian Government to look only after Indians residing in East Africa while continuing to retain their citizenship of India.

He would expose his motivation (deriving from Nehru) much later as follows: “The existence of these populations of Indian origin was the obvious justification for my job. At the same time it was natural that the representative of an independent India would not see this job with the same eyes as a servant of the former British Raj, which had also an official concern with overseas Indians, in Africa and elsewhere. One could not forget that Gandhi had begun his life’s work as champion of the Indians in South Africa against discriminatory laws, that he had done so as a citizen of the British Empire appealing to the rights which he believed it guaranteed; and that later he had hoped and foretold that national freedom for India would open the way to liberation of the weaker peoples of the earth.” (1974; p. 49/50). There is here, in my view, a purposefully breathtaking, if somewhat specious, conflation of situations and roles that Pant apparently felt to be self-evident.

In pursuing his mission, therefore, Pant was likely able initially with his personal charm to court with substantial success most of the Asian communities’ leaders of the day, be they politicians, businessmen, journalists, and professionals. Among such political leaders were: the presidents of the East African Indian Congress (EAINC) during his tenure such as D.D.Puri and

J.M. Nazareth, as well as former presidents such as A.B.Patel, N.S. Mangat, S.G. Amin, Chanan Singh, Chunilal Madan; Muslim leaders such as Shams-ud-Din, Eboo Pirbhai, Chairman of the Muslim Central Association and Ibrahim Nathoo (both Ismailis), Bhagat Singh Biant of the East African Ramgharia Board (Sikhs)t, Dr. A.C.L de Souza of the GOA (Goan), and Messrs. A.H. Nurmohamed and Y.E. Jivanjee (Ithanasheri/Bohra). His courtship also extended to businessmen and professionals such as: Suryakant Patel, the Chairman of the Seva Dal, G.L.Vidyarthi, Mohamedalli Rattansi, Inder Singh Gill, Muljibhai Madhvani, Nanji Kalidas Mehta, R.B. Pandya, R.K. Paroo, J.M. Desai, Dr. S.D.Karve, Dr F.C. Sood, John Karmali and many others. Not surprisingly because of Makhan Singh’s political peruasion and his security status, Pant appears to have had only a perfunctory and marginal contact with him, although in a sense Makhan Singh was the only Asian-born politician whose views matched up anywhere close to those of Pant himself. Nor from his books, is it clear that Pant had met with Ambu Patel, who in a Gandhian fashion “single-handedly publicized the unjust incarceration of Jomo Kenyatta.” (Seidenberg 1996, Ch. 6; p. 25). It is understood, however, that he encouraged the setting up, and assisted at the opening of, the Republic High School by Dr. A.U.Sheth in Mombasa in September, 1951 as a multi-racial school with fees underwritten on the basis of need, based on the earlier attempt with John Karmali with what developed later into the well-known and still existing Hospital Hill School.

Pant’s approaches, as noted above, initially found a very receptive ear among Asians as a whole, in part because they had no reason or alternative for not giving him the benefit of the doubt. One of the first signs of concern, however, comes in April 1950 when, at the first joint meeting of KAU (headed by Kenyatta) and EAINC (headed by Nazareth), one of the speakers quotes provocatively from an earlier statement of Nehru to the effect that Indians in Africa must generally regard themselves as “guests” of the Africans – as noted later, a climacteric personal moment for Nazareth. In addition, Hindu/Muslim agitation for separate voting rolls, although simmering below the surface especially among the Punjabi Muslims (Dr. Rana and Allah Ditta Qureshi), had not yet fully infected Asian leaders in Kenya who continued to operate largely within the cooperative harmony engendered by an earlier generation of Asian leaders. Even the Aga Khan had reportedly advised his Ismaili followers in March 1948 not to create Hindu-Muslim quarrels by bringing India’s, Pakistan’s and Hindustan’s quarrels into East Africa but rather to live as one in unity and be known as East Africans as therein would lie their salvation. In line with this position, in March, 1950 Ibrahim Nathoo roundly criticized Qureshi, the Secretary of the Muslim Central Association, for having on his personal initiative sent an unrepresentative memorandum purportedly on behalf of all Muslims in Kenya directly to the Pakistan government; he followed this up in the same month reception for Pant by stating that it was undesirable to import disunity from the Indian subcontinent to Kenya. The traditional, decades-long, obstacle for all Asians had remained, since the founding of Kenya Colony and Protectorate, the racial attitudes of the European farmer/settler, who had refused pointedly to entertain the Asians legitimate claims for racial nondiscrimination in social and economic life as well as parity of representation in the organs of government.

Pant also initially exerted a great charm on the general social circuit in Nairobi, in particular with Europeans who viewed him somewhat romantically as a different type of Indian, a suave Oxford-educated prince no less. But this soon faded, as Pant notes: “My well-known alleged --and real—sympathies and friendships with Africans (emphasis supplied) had made me almost an outcast in the social life of the white inhabitants. Except for a few real friends like Sir Berkeley Nihill, the chief justice of Kenya, Derek Ersikin, a big landowner, Sir Vaisey and a few others who could be counted on the fingers of one hand, the official circles had decided to boycott all functions at the Indian Embassy (sic) and did not invite me to theirs.” (Pant 1987; p.23). Moreover, and below the surface, as the intelligence reports suggest, the local European community of officials and settlers exhibited growing alarm about his activities, incorrectly but fearfully viewing him as a essentially a stalking horse for the introduction into Kenya of the growing worldwide influence of India and Nehru.

That nothing came of their protests was probably due to the fact that a Labour Government was in power in the UK through November 1951 and its leaders had strong personal connections to Nehru and an overarching interest in reformatting the British Commonwealth to enable India upon becoming a republic in January 1950 to stay within it, and Nehru was the key to the success of this endeavor. This bias was complemented at the local level by the then Governor of Kenya, Sir Philip Mitchell, in office during his Pant’s first four years perhaps because the former was no doubt aware of the stakes in London, and with whom Pant in any case apparently had, at least on the surface, a good working relationship, as two former Oxford men notwithstanding the considerable difference in their ages. Pant notes, for example, that the Governor looked with reserved favor at his setting up (with John Karmali and Hassan Nathu) a private school for all races in his own house, although balking at a larger and more permanent establishment of this nature (Pant 1978; p.54)

This visceral fear among Europeans for Indians was linked to India’s growing importance in the world and is amply exposed by short quotations from four statements made much later in October, 1954 in the context of the introduction of a more balanced multi-racial government and a “truce” agreement between the three major groups of European opinion (the European Electors Union, the United Country Party, and the Federal Independence Party and that arch anti-Asian politician from a previous generation, octogenarian Colonel Ewart Grogan) to resist the deepening multi-racial legislative plan drawn by the new Colonial Secretary Lennox Boyd:. The last mentioned, in a letter to the Economist, in December 1954 wrote to the effect that: “We resent the blatant inconsistency of imposing part Indian rule over our Africans and Arabs without our consent…. If the straight issue ‘Are you willing to be ruled by Indians?’ could be put to (them), the answer would be an universal and emphatic No!!”. Another similar statement came from the Earl of Portsmouth who baldly asserted in October 1954: “There is really only one real cleavage between us: to what extent shall India’s influence carry here?” Mr. S.V. Cooke also asserted: “I am all out for racial cooperation. That does not mean I am determined or prepared to give authority to Asians in this country – and more particularly the Indians”. Mr. Coller-Hallowes echoed this line with: “Unless we say that we are going to join up and go forward to help the African and the Arab in this country at every opportunity, we are going to face the issue that this country has been handed over to the Indians”.

As noted above, Governor Mitchell fully cognizant of London’s standpoint exerted a countervailing presence at the local level, helping to contain the settlers protests.. During his eight year tenure ending with his retirement from the Colonial Service at end June 1952, Mitchell identified closely with all communities in Kenya. I believe that he had gradually developed a confident and prescient multi-racial cast to his thinking born of some 40 years of prior colonial experience in the East African countries themselves (1919-40) and subsequently with countries with mixed populations, notably with Indians in Fiji from where after 8 years he had come to Kenya in 1944. There are some who hold to the view from an exchange of telegrams between the first Labour Colonial Secretary (Creech Jones) and Governor Mitchell soon after they had come to power in November 1946, that the new authorities had grave reservations about Mitchell’s attempt with Sessional Paper No.3 of 1945 to increase the executive responsibility of Europeans to the detriment of Non-Europeans generally, and to follow this up by attempting to dilute the Asian representation through the specific acknowledgement of Hindu/Muslim disunity.

If this were his initial motivation, however, once the Labour government was more fully in the saddle, he would had to have fallen into line with the new more strongly anti-colonial thinking coming out of London from his new political masters, inasmuch as Colonial 191 reserved final responsibility for the overall policy and administration of the East African territories firmly in the hands of the Imperial Government. I thus believe that he would been compelled to accept Labour’s thinking onin the need for communal rolls and not a common role in helping to bring about an eventual multi-racial society in Kenya based on majority rule and governance by moderates of all three races. Where he may undoubtedly have differed from London would be less on the direction of the change (over which he had no control) and more on the pace of change (over which he had control), designed to ensure that the process, whilst it could be accelerated in policy terms, should not be unduly rushed in operational terms..

In the event, and with London’s backing in those financially austere years, he helped push through a raft of administrative and logistical proposals to undergird an evolving multiracial society in Kenya. These included: the formation of the East African High Commission (1947) and East African Legislative Assembly (1948); the founding of the Muslim Institute (MIOME) in Mombasa in March 1950; the establishment of the East African Court of Appeal in January 1951; encouraging the formation of the United Kenya Clubs in Nairobi and Mombasa (July 1951) open to all races by allocating choice land; laying the foundation stone of the multi-racial Royal Technical College in April 1952; and finally and perhaps most importantly, agreeing to a six month extension of his term to shepherd through the run up to the general elections in early June 1952, based on the multi-racial Lyttleton Plan hurriedly put together by the new Conservative Secretary Humphrey Lyttleton after a visit to Kenya in January 1952, which accepted for the first timed for the first time a parity between Europeans and Non Europeans at the “unofficial level”. On the other hand, his biggest mistake was probably to downplay in reports to London the severity of Mau Mau secret oathing threats that had commenced over a year before he left. --- even to the extent of permitting, against the advice of his security officials, the visit to Kenya of Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh in early February, 1952 --- because he did not want to have to deal with the Mau Mau threat on his watch. Upon retirement and following two months of paid leave in September 1952, he chose not unsurprisingly to settle on his farm in Kenya until his passing away in 1964.

I believe too, as previously noted, that Mitchell had a fairly comfortable working relationship with Pant, favoring him with a fair degree of access and relatively free rein within the bounds of quasi-diplomatic propriety. This relationship was especially tested --as Pant ruefully notes -- when Lady Mountbatten, as Superintendent-in-Chief of the St John’s Ambulance Brigade, a member of the British Royal Family by marriage and a close confidante of Nehru, first visited Kenya in February 1951 and was invited by the Governor to stay at Government House. (Coincidentally, I believe that at that material time her younger sister Mary was in fact still married to the 4thBaron Delamere, and could in principle have been invited to the reception). At a reception in her honour, she pointedly noted to the Governor and Pant that the invited guests were largely of European “official” and “unofficial” groups, with only a miniscule number of handpicked non-Europeans. She then remonstrated that because of her charitable activities she needed to meet a much wider representative and balanced racial cross section of the population, which the Governor suggested would not be feasible at short notice. To his and Pant’s huge surprise and discomfiture, she thereupon calmly announced that in these circumstances she would move out of Government House and into the Pants’ residence for the last couple of days of her stay. As Pant himself notes, this short notice created considerable logistical difficulties for him; moreover, at a subsequent party in his house to which Pant invited 25 prominent representatives each from the European, Asian and African communities, only one European, the chief of the security police, turned up!!

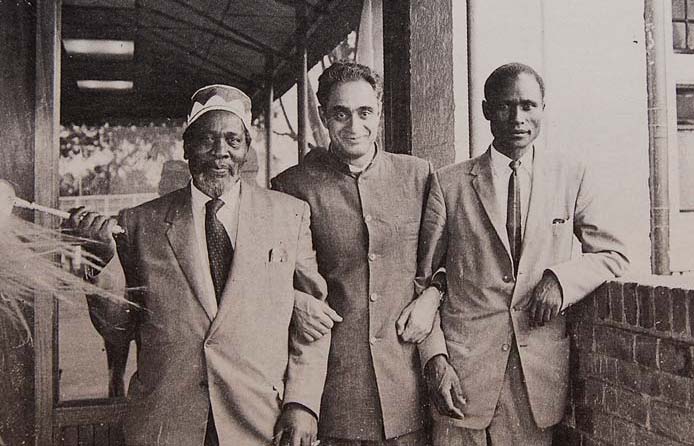

Pant’s dealings with African leaders undoubtedly represented the main thrust of his activities in Kenya and East and Central Africa more generally. The message he brought them from Nehru was naturally music to their collective ears, although here too his real contact was limited to the Kikuyu, and specifically to Kenyatta and the Koinanges. It seems very likely that beyond this, and given his diplomatic position, he could only keep abreast of the evolving situation not through any Asian politician but through the conduit of the lone Asian operator, Pio Gama Pinto. At the international level, and in order to buttress the representations made by India, as the recognized leader of the anti-colonial and nonaligned world, Nehru had apparently arranged for Pant to be co-opted into the Indian delegation to the United Nations led by its internationally known ambassador Krishna Menon, starting in 1951 in Geneva and Paris, and then New York in 1952 onwards. With his unrivalled knowledge of local conditions on the ground It would appear that Pant’s role would be to participate in both the Decolonization and Trusteeship Committees at the United Nations.. Two significant indications of India and Pant’s indirect influence through Nehru’s connections, as these applied to Tanganyika as a UN Trust Territory, were: first, the new Conservative Government respected an earlier Labour government undertaking and in July 1952 permitted Sir Edward Twining, the Governor of Tanganyika, to give evidence for the first time before the Trusteeship Council of the United Nations; second, Julius Nyerere, as the newly elected President of the Tanganyika African Union (TANU) was also permitted to give direct evidence for the first time to the Council in late 1952/early 1953.

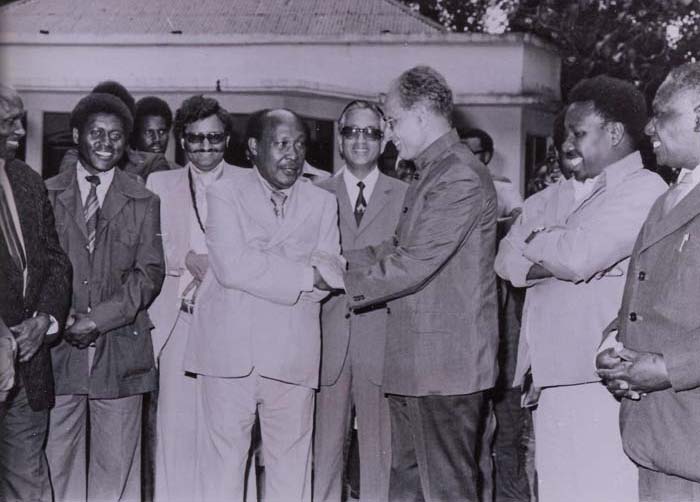

Complementing his indirect international activities on behalf of the African cause, Pant also showed his concern in several direct ways at the local level, while at all times having to be extremely careful because he was being closely monitored, despite his relationship with Governor Mitchell. This enabled him, for example, to arrange on June 23, 1951 for Jomo Kenyatta and Mbiyu Koinange to be officially welcomed and feted in Mombasa on board the visiting Indian warship HMS Delhi. Later, following the arrest in October 1952 of Jomo Kenyatta and six other associates and the proscribing of the Kenya African Union (KAU), Pant no doubt arranged for Joseph Murumbi, Acting Secretary of KAU who had fled from Kenya into exile in March 1953 to escape arrest, to meet the Indian President and Prime Minister as the external representative of KAU and to be financially supported for several years in the UK, and for Nehru to send Dewan Chaman Lall to take part in Kenyatta’s legal defence team.. He also arranged for a scholarship scheme (up to 30 in number) at Indian universities to be instituted for deserving African students (e.g those expelled from Makerere University College in June, 1952 after a student strike such as Dr. Joseph Karanja, who later rose Vice President of Kenya, Omolo Okero who became a Minister, and Joseph Gataguta, a Member of Parliament); in this endeavor, he was aided by his close and long-standing friend Peter Wright, who after he had been deported in November 1952 from Kenya, was invited by Nehru on Pant’s recommendation to create and head an African Studies program at Delhi University.

The thrust of Pant’s activities on behalf of African freedom, however, came from his direct support of the liberation fight. Very soon after his arrival in October 1948, he had been introduced by S.G. Amin to Peter Mbiyu Koinange, the brother in law of Jomo Kenyatta and eldest son of Senior Chief Koinange-wa-Mbiyu. When Pant’s father visited him in Nairobi in 1950, Pant had taken him along to meet with ex-Senior Chief Koinange at his home in Githinguri. Much later in August, 1951, just after he had returned to Nairobi from an extended visit to India in connection with the death of his father in Aundh, the progressively closer personal relationship with Pant with the Koinanges would be deepened by his “adoption” as a Koinange; it would be fully consummated in a subsequent dead-of night ritual ceremony when he was inducted with the assistance of Pinto, as an elder into the Koinange clan.(1987; p.27/28). Much later, but with less secrecy on their part and less weight attached to this on his, Pant would also be inducted as an elder into the Kamba and Luo tribes

In any case, at this stage, the African political and trade union leadership, both within the Kikuyu heartland and elsewhere, was desperately in need of all kinds of assistance from whatever quarter it came. More ominously in the Kikuyu heartland secret oathing had commenced, encouraged it was suggested not by the Koinange family or Kenyatta through KAU, but by the more radical elements (such as Fred Kubao, Bildad Kaggia) who they could not control, through the formation of the so-called Kiambaa Parliament. By its very nature, support for such activities from whatever source had to be provided in a surreptitious manner, and there is little concrete information of whether this took the form of money and/or materiel (arms), and if so to whom and how it had been channeled; it is reported, however, that in the early 1950s Pinto did help to organize and sustain a secret Mau Mau War Council, as it was termed, in Nairobi. In this connection, it is interesting to note Pant’s mention that when he was away visiting the Belgian-Congo, a security detail was able to gain access to his basement in a fruitless search for arms stored, and later also that both Nehru and Indira Gandhi privately knew how much Pinto had done for the African cause. (Pant 1987; p. 25-27) There appears, on the other hand, to be some plausible indication that Pant focused on building up African capability in journalism by persuading existing Indian newspapers to help out and through provision of equipment and materials (for example, it has been suggested that he persuaded The Daily Chronicle to assist Asya Awori with the printing of his vernacular newspaper).

It is incontestable, and this is confirmed by Pant himself, that starting in about late-1950 and through the rest of his tenure, a central figure in Pant’s ability to operate under cover with the African (mainly Kikuyu) leaders was Pio Gama Pinto because of the latter’s extensive knowledge of the inner workings of the African trade union movement and political groupings through continual interfacing and his remarkable discretion. Working out of the EAINC office with Pant’s tacit support, Pinto was able to acquire such knowledge and acquire their unquestioning loyalty and support by sheer dint of exhibited commitment and prodigious effort that he was able to muster. Indeed, it is probably safe to say that without Pinto’s willingness to assist Pant in developing his mission to promote the African cause, while remaining the soul of discretion and thus entirely trustworthy, Pant’s forays into this area would have been greatly minimized, especially from the second half of 1951 onwards.

TERMINAL PHASE (January 1952 – February 1954)

By the first quarter of 1952, the situation that confronted Pant had changed quite swiftly in an entirely adverse direction ---. Nehru was increasingly turning his attention away from anti-colonial matters in Africa and towards developing firmer links with the non-aligned world (including China); the Conservatives under Churchill had ousted Labour from the government of the UK in November 1951, and Oliver Lyttleton had been appointed Colonial Secretary with Alan Lennox-Boyd as his junior Minster committed to introducing some form of a multi racial legislative system in Kenya; Governor Mitchell was focusing exclusively on the introduction of this system following a general election scheduled for June 1952 after which he would proceed on retirement; Asians had come slowly to realize that their earlier expectations about Nehru and Pant were overblown and that India had always been more interested in helping the African majority attain independence than helping Indians in their perceived predicament; amongst Africans (especially Kikuyus) -- and indeed for the whole of the country generally – Mau Mau had begun to exert its deleterious effects on all aspects of life, and Pant’s main contacts were shortly to be imprisoned as the British fight back assumed major proportions. In this environment, Pant appeared more than ever to be reduced to being an utterly reactive spectator rather than a modest proactive player, because he was wholly unable to influence any other of the major players in either official or unofficial political circles in Kenya.

The central phenomenon for the rest of Pant’s stay and even beyond, in regard to which he became a mere onlooker, would be the trial of strength between a largely Kikuyu-based tribal onslaught and the massive British response; it would lead in due course to a significant reordering of interactive relationships between all the players on the Kenya political scene dividing tribal clan from clan, tribe from tribe and even race from race. It even produced unusual tension between a realpolitik pragmatist like Nehru and a Gandhian idealist like Pant. As Pant notes wryly: “ The terrorism and violence of the Mau-Mau campaign came as a personal shock to me, as well as an obstacle to our efforts … I did not conceal my reaction to them and in consequence earned a reprimand from Nehru ..(who).. exploded in anger at my failure to distinguish between “imperialistic” violence and that of the “freedom struggle”. Once or twice he nearly threw me out of his office because I was harping, unnecessarily as he judged, upon outrages committed in the name of freedom” (Pant 1978. p.26). Pant goes on to state: “ ..I talked often before their internment about tribal life in all its aspects, above all in reference to the freedom struggle. Many of our discussions centered upon the question of violence: was it necessary, was it avoidable, was it profitable? I feel sure that if cross fertilization of Indian experience in this context had taken place ten years earlier the struggle in this part of Africa would have been different”.(Pant 1978; p.28). This quote is revealing because Pant does not provide any indication of the reactions, which certainly could not have pleased him, hence the escape from the real “what has to be” to the more counterfactual fantasy of “what might have been, if.”